The Stories and Science Behind the Plague of Fugitive Gravel Road Dust

Google “residents complain about road dust” and you’ll get over 17 million results, with lists of local news articles citing community complaints about the detrimental effect of gravel road dust.

If you’re a county or municipal official who has anything to do with county or township road management, you’ve probably heard all of the stories:

- Dust gets in air conditioners

- It coats everything, from cars to windows

- It gets into the engines of cars, congesting them, while damaging bearings, all increasing repair costs

- Asthma sufferers and the elderly can’t even spend time outside

- Opening windows during the heat of summer leads to dust getting on everything in the house

One resident of Limestone County, Alabama said “The water truck stops for lunch and before he gets back, there is dust everywhere. Over the weekend and on the holiday, we had to eat dust. It’s destroying our properties and houses.”

And from Sioux City, Iowa: “My kids can’t play outside.” And, “We’re just fed up. You can’t breathe.”

A resident in Robinson, Texas complained, “It’s hard to even come outside…. You can’t see ahead of you.”

These comments create a dilemma for local authorities, whose hands are tied by funding and budget restraints and who can’t afford the equipment and upgrades residents are demanding.

But as difficult as limited budgets make it to resolve these complaints, the scientific evidence that has emerged in greater and greater volume over the last couple of decades makes it clear: fugitive gravel road dust is a serious threat, to the health of both our communities and the environment.

The 2007 Environmental Protection Agency handbook Environmentally Sensitive Maintenance for Dirt and Gravel Roads asks dirt and gravel road managers to think differently about our rural roads:

“We need to initiate a change in this thinking. We can no longer afford to think only about the road. We need to understand the relationship between the road and the environment, that everything is interconnected, and that there are practices that are not only good for road, but also good for the environment. In addition, we need to make the connection that both good roads and a good environment are important to the welfare of local governments and their residents.”

But it’s not just about the benefits to the environment or local communities. The handbook argues that this new way of thinking has plenty of benefits for the roads themselves:

“…roads maintained in an environmentally friendly way have more structural strength, suffer less deterioration and have fewer defects, and, thereby, are also safer. The goals of low-cost, environmentally sensitive road maintenance and improved road safety can be combined seamlessly.”

So this article takes a closer look at the connection between our unpaved roads, communities and environment, with a specific focus on the negative effects of fugitive gravel road dust.

The Scale of Fugitive Dust

The EPA’s Environmentally Sensitive Maintenance for Dirt and Gravel Roads handbook (citing an earlier maxim from a USDA Forest Service publication in 1983) reminds us of what we could call the “rule of one”:

“One car making one pass on one mile of dirt or gravel road one time each day for one year creates one ton of dust.”

(A gravel road with an average daily traffic volume of just 100 cars can be assumed to be putting out 100 tons of dust per mile, per year. Think about that.)

The earlier Forest Service publication clarifies that the dust is deposited along a thousand foot corridor centered on the road (cited in this study). Meaning the majority of gravel road dust is moving as far as 500 feet from either side of the road, covering everything in its path (from vegetation to homes).

However, this doesn’t fully do dust justice.

A number of forces are at work to move dust. Turbulent mixing and convective updrafts work to lift dust higher into the atmosphere. Gravitation works against these to bring the dust back to earth. But meanwhile, wind has the opportunity to help it spread.

The work of gravity on dust means that larger, heavier particles are deposited first. Smaller particles, however, travel further. While particle sizes over 10 micrometers in size (PM10) can stay in the air for hours, particulate matter under 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) can stay in the air for more than 10 days. Given the space, wind can carry these micro particles hundreds of miles.

(This fact, of course, emphasizes the critical role that the environment, specifically vegetative cover, can play in reducing the movement of dust.)

We’ve covered the sheer volume of dust being carried off our unpaved roads as well as the distance it can travel. But how our roads are used can play a huge role in shaping the volume of dust being lost from roads.

For many counties and townships, traffic volume on unpaved roads is increasing, sometimes dramatically. Sometimes, this is due to population growth, and therefore more residential usage of the roads. Other times, it’s from the expansion of industries in the area, such as mining, gas/oil production, logging, agriculture and tourism.

Given that the three biggest impacts on the loss of dust particulate matter from dirt and gravel roads are traffic volume, traffic speed and traffic weight, it’s easy to see how these changes can impact the amount of gravel road dust in our communities and the environment.

One study found that the difference in volume of dust produced between a road with higher traffic volume versus lower traffic volume is an extra pound of dust per square meter (up to 10 meters from the road side; see page 37 of the study).

Imagine this over a mile of road surface. Assuming a “wide granular” type of road (28 feet wide) capable of serving between 50-124 vehicles per day, the surface area of one mile of road is about 13,735 square meters.

What does this mean? If your county or township has seen a significant rise in traffic over the years, this could be producing as much as seven tons of additional gravel road dust per mile.

Suffice to say, our dirt and gravel roads are putting out a lot of dust. But what is the impact of this dust?

Gravel Road Dust and People

The biggest factor in how dust particles affect human health is size. Particles larger than 10 micrometers (commonly known as PM10) aren’t breathable, so only affect external organs. These particles are major eye and skin irritants, including causing conjunctivitis and increasing the susceptibility to ocular infection.

Inhalable particles, those under PM10, get trapped in the nose, mouth and upper respiratory tract, leading to conditions like asthma, tracheitis, pneumonia, allergic rhinitis and silicosis.

These two levels are what people feel, and what many of their complaints to local officials are about, from the damage to homes, vehicles and properties to the health effects.

The finest particles, known as PM2.5 (less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter), get deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream. Here, they can affect all internal organs and lead to cardiovascular disorders. One global assessment from 2014 estimated that dust exposure may have led to over 400,000 deaths around the world from cardiopulmonary diseases in the over-30 age group.

If you are getting complaints from your residents about gravel road dust affecting their health, the reality is that more may be going on under the surface that even they don’t realize. Take these complaints seriously!

If all of this isn’t bad enough, dust also serves as a carrier.

Last May, we published an article on new evidence that coronavirus particles attach to dust particles in heavily polluted environments, causing it to spread further. Our research drew from studies in northern Italy, where, after controlling for population size, higher rates of coronavirus spread were linked to higher pollution levels in the most industrialized part of the country.

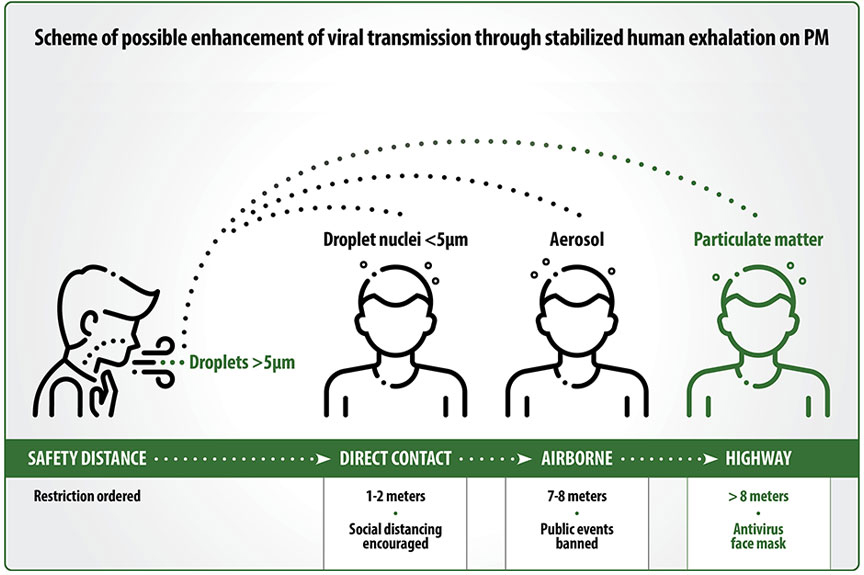

Any activity, such as speaking, coughing, sneezing, etc., spreads droplets of saliva. Larger droplets, over five micrometers in size, usually settle within three to six feet (hence the six-foot social distancing standard). Smaller wet particles, called aerosol, can travel as far as between 20-25 feet.

But the smallest particles can actually attach to the drier dust particles in air, essentially piggybacking along as far as those smaller dust particles can travel. Think anywhere from several dozen feet up to miles.

Figure 1 How viral particles can be spread further by dust particulate matter.

But COVID isn’t the only disease that can travel on gravel road dust particles.

As an extreme case, to demonstrate the point, take meningococcal meningitis. A bacterial infection of the tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, meningococcal meningitis causes brain damage, as well as death in 50% of untreated cases.

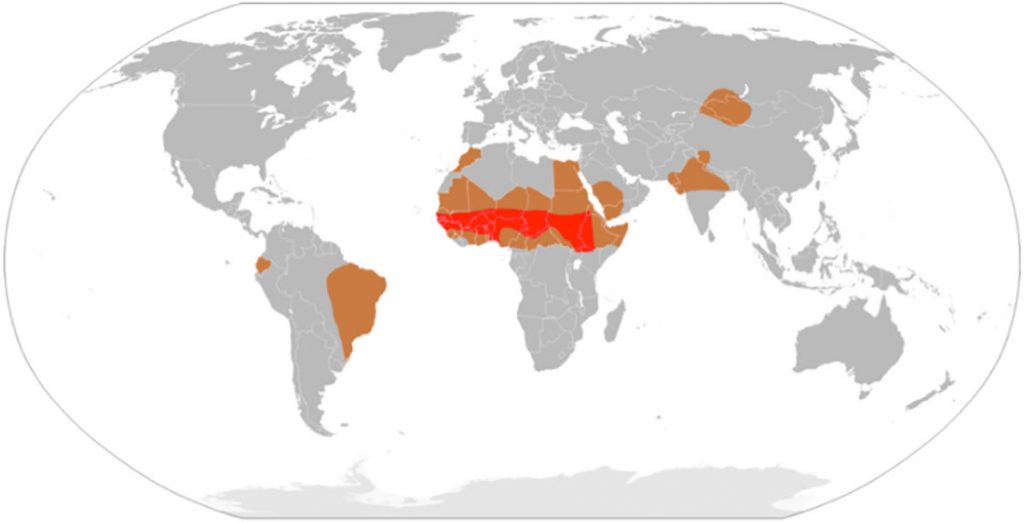

The highest incidence of outbreak occurs in a stretch of central Africa known as the “meningitis belt” – an area with an estimated population of 300 million.

Figure 2 Map of meningitis belt (in red) and regions at high risk of epidemics (brown). (Source)

Several studies have linked the areas of highest outbreaks to seasonal patterns of low humidity and dusty conditions. (Not only do the dust particles help spread the disease; they also contribute to creating favorable conditions in the throat and mouth for bacterial infection, by damaging moist tissue [mucosa] in these locations.)

To bring this closer to home, in the southwest of the U.S. and in northern Mexico dust has played a role in transporting Coccidioides fungi spores, which cause valley fever, a potentially deadly disease.

Finally, in addition to infectious diseases, dust can also carry traces of toxic metals. In the meningitis example above, researchers believe iron oxides embedded in dust particles may enhance the risk of infection.

In a 2018 study in Gary, Indiana, researchers found high levels of dangerous heavy metals in the road dust. These included lead, zinc, chromium, copper, vanadium and manganese. The location was chosen because of its similarity to many urban areas around the world: a medium-sized, formerly heavily industrialized city. The presence of metals in road dust demonstrates that these materials remain in place years after the reduction of industrial activity.

Studies have found heavy metals in dirt and gravel road dust all over the world, from Pakistan and Japan to Ohio and Pennsylvania, in urban and rural environments. Sources include bits of car tires, brake materials, soils, churned-up asphalt and residual metals from industrial activities.

To reiterate, if your residents are complaining, listen. You don’t know how badly gravel road dust might be harming them.

Gravel Road Dust and Society

In addition to health, dust has a negative impact on local economies.

On a personal level, as we saw in many of the common complaints by residents in the introduction to this article, dust damages vehicles and other equipment, hurts gardens and necessitates extensive cleaning and even landscaping. All of this raises the local cost of living, for a lowered quality of life.

Going a step beyond this, vulnerable populations especially can see a rise in medical costs as they cope with the diseases and other health problems caused by gravel road dust.

Commercially, dust problems decrease tourism, reduce agricultural revenue (from ruined crops), increase the cost of healthcare and exacerbate local infrastructure issues. Dust clouds create visibility issues for pilots and drivers alike, affecting both land and air transportation. Deposits on solar panels reduce efficiency by blocking incoming sunlight from reaching the panel, requiring greater labor costs to harness the same amount of energy.

Gravel Road Dust and the Environment

Remember the literally tons of dust being kicked off your dirt and gravel roads? Well, when it’s not blanketing homes, properties and people, it’s landing on vegetation and in local waterways, spreading the contaminating effects even further.

Larger dust particles physically smother plants’ pores, while smaller particles restrict gas exchange. In both cases, this hurts photosynthesis, thus stunting plant growth. That particularly effects vulnerable plants such as lichens and mosses. Vegetation becomes more vulnerable to pathogens, insects and heavy metals (which, of course, are also being carried by the dust to the plant). All of this leads to a reduction in biodiversity, as native plants are reduced and hardy invasive species move in to take over.

This reduction in native vegetation also has the effect of causing soil erosion. And as dust settles, along with the accompanying toxic heavy metals, it creates an imbalance in nutrients and pH levels in the soil. The combination of these effects creates a negative feedback loop with eroding vegetation, increasing the rate of ecosystem decay.

These effects on vegetation and soil also apply to agricultural land, causing damage to crops and ruining topsoil.

Dust that settles on water sources, such as streams and wetlands, contaminates the water, increasing sedimentation, altering the nutrient makeup and increasing algal biomass. This can have a toxic effect on aquatic life. Contamination then spreads to surrounding water sources, including getting into the ground water.

Wildlife are affected by the respiratory effects of breathing in smaller particle sizes. Also, as native vegetation is destroyed, they lose breeding and nesting sites as well as sources of food and shelter.

Common Dust Control Solutions Don’t Cut It

The most common efforts to control dust on dirt/unpaved and gravel roads include regular watering and the use of chlorides. (See the EPA handbook referenced above for more information on dust control options and the pros and cons of each.) However, these methods create an “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” effect – with the dust at least temporarily reduced, it’s hard to see how the local environment and community are still negatively affected.

Watering seems straightforward enough. You wouldn’t expect much in the way of negative health and environmental effects from water.

However, water is an extremely short-lived option. Water trucks need to be watering constantly during hot summer months to keep dust levels sufficiently low, as water evaporates in as little as a lunch break for the driver. So the first problem is the constant required use of trucks.

Like mentioned earlier, increased traffic volume is one of the biggest causes of higher levels of fugitive dust. Additionally, the more activity from heavy trucks you have on your roads, the quicker they begin to break down. Dust particles, or fines, are the glue that hold the aggregate of the dirt or gravel road together. As fines get kicked up, the larger aggregate breaks down, causing the road itself to disintegrate.

Heavy rains can wash these loose fines and aggregate out of the road; but all the water you’re spraying can help with that. Essentially, you might be gradually washing your road away, including spreading dust and aggregate into the environment around the road.

The second problem is an extension of the first: any toxic metals in the gravel road dust can be washed into the environment or community.

Finally, if the water is drawn from public sources, it likely contains chlorine. If a large enough amount is dumped in nearby water sources, it could negatively affect aquatic life.

Other common dust control options include the chloride family: sodium, calcium and magnesium chlorides. While the sodium, calcium and magnesium attach to other materials, the chlorides become free agents and leak out of the road into nearby vegetation, streams, ground water sources and people’s yards.

Chlorides are corrosive to metal (as any northerner can attest during winter, when their car becomes caked in road salts), leading to, once again, equipment repair costs for individuals and government agencies.

They are also harmful to vegetation, primarily by accumulating on leaves and blocking photosynthesis (similar to dust particles). Eventually this causes leaf burn and die back. Ultimately this creates a similar cycle of events to dust accumulation on the roadside: a reduction of native plants creates soil erosion and introduces invasive species, while the nutrient and pH balance of the topsoil becomes unbalanced. This then impacts local wildlife.

A Better Option for Dust Control

Midwest has spent decades having conversations with local communities and studying the interaction between unpaved roads, communities and the environment.

We have constantly innovated in bringing new products to market that best fit this intersection. Our product line has a range of third-party verifications for being safe for the environment and human health. Rather than leaching from roadways like so many other generic products, our products have a compounding effect: they bind to the soil in such a way that increased usage actually makes the road stronger.

But we go beyond simply being a product manufacturer. After decades of work in this industry, we approach these challenges as a strategic partner, as a problem solver, to our clients. We step in to help them design a customized, comprehensive dust control program, from initial assessment and custom product recommendations, to experimenting with application to get the desired results, to tracking those results long after the initial application.

Midwest embodies the challenge from the EPA handbook referenced at the beginning of this article, that we should be looking at the way roads, the environment and our communities interact, rather than at the road alone.

At Midwest, we call this the Third Way – a different way of thinking about things, the only way of truly creating a win-win-win situation for all stakeholders. And only Midwest is uniquely positioned to help our client-partners achieve this.

Click here to learn more about the gravel road dust solutions Midwest can provide for your dirt and gravel roads.